David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, creators of HBO’s Game of Thrones, are already working on their next big project, an alternate history in which the Civil War did not end with the United States defeating the Confederacy and reuniting the nation. The show will be called Confederate, and includes writers Nichelle Tramble and Malcolm Spellman. The proposed show has been a hot topic of conversation among my social circle, especially my historian friends.

This show is terrible idea. I am a GoT fan, but I fully acknowledge that the show has serious issues in how it presents violence, especially sexual violence, particularly against women. In some cases, scenes representing consensual sex in the text are filmed as rape. Plenty of viewers abandoned the show after that moment (if they hadn’t already), and I actually spent the entire season reading recaps before deciding if I wanted to watch each episode. My point here is not rehash these scenes, but to point out that Benioff and Weiss have done nothing in their largest, most popular project to convince me that they are capable of handling sensitive subjects with grace or thoughtfulness. Since rape was a critical part of the institution of slavery, I am deeply concerned about their ability to engage with that in a thoughtful, non-salacious way (which 12 Years a Slave did very successfully).

This show is terrible idea. I am a GoT fan, but I fully acknowledge that the show has serious issues in how it presents violence, especially sexual violence, particularly against women. In some cases, scenes representing consensual sex in the text are filmed as rape. Plenty of viewers abandoned the show after that moment (if they hadn’t already), and I actually spent the entire season reading recaps before deciding if I wanted to watch each episode. My point here is not rehash these scenes, but to point out that Benioff and Weiss have done nothing in their largest, most popular project to convince me that they are capable of handling sensitive subjects with grace or thoughtfulness. Since rape was a critical part of the institution of slavery, I am deeply concerned about their ability to engage with that in a thoughtful, non-salacious way (which 12 Years a Slave did very successfully).

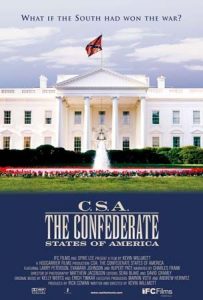

I also wonder about the point of this. Alternate history, like regular history, is often about social commentary. What is the commentary value gained here? I’ve seen the Confederate States of America mockumentary, which supposes the South won and makes scathing commentary on race relations. In the case of Confederate, I’m unsure what would be gained. Supposing the South could have won is deeply counterfactual; while slavery remained profitable, the South lacked the necessary infrastructure to sustain a war effort. Desertion became a serious problem as yeoman farmers and poor whites realized they were fighting not for some lofty dream, but for the ability of the rich man to build his wealth through human property at the expense of poor farmers. Supposing that the South could have won is a dangerous engagement with the Lost Cause narrative and the century(ies) of white supremacy and anti-black terrorism it fed/feeds.

I also wonder about the point of this. Alternate history, like regular history, is often about social commentary. What is the commentary value gained here? I’ve seen the Confederate States of America mockumentary, which supposes the South won and makes scathing commentary on race relations. In the case of Confederate, I’m unsure what would be gained. Supposing the South could have won is deeply counterfactual; while slavery remained profitable, the South lacked the necessary infrastructure to sustain a war effort. Desertion became a serious problem as yeoman farmers and poor whites realized they were fighting not for some lofty dream, but for the ability of the rich man to build his wealth through human property at the expense of poor farmers. Supposing that the South could have won is a dangerous engagement with the Lost Cause narrative and the century(ies) of white supremacy and anti-black terrorism it fed/feeds.

I’ve seen people defend this project by comparing it to The Man in the High Castle, a dystopian show about what life might be like if the Axis Powers had won World War II. I haven’t yet seen the show, bu t there are significant differences between Nazi Germany and slavery in the United States. Without engaging in some sort of misery Olympics, the duration alone should give anyone making this comparison pause. While we are far from done dealing with Nazism and its consequences, I think it’s fair to say that we have made significantly more progress in engaging with it than we have with centuries of chattel slavery in the United States.

t there are significant differences between Nazi Germany and slavery in the United States. Without engaging in some sort of misery Olympics, the duration alone should give anyone making this comparison pause. While we are far from done dealing with Nazism and its consequences, I think it’s fair to say that we have made significantly more progress in engaging with it than we have with centuries of chattel slavery in the United States.

If you disagree, consider how we approach sites of memory for each. Concentration camps are sacred spaces, full of monuments and solemn visitors. Plantations, the forced labor camps of the antebellum South, are wedding venues. Holocaust denial is shameful, while referring to enslaved people as servants and downplaying slavery and its long-term impacts are commonplace. White people routinely claim that slavery was not that bad, that African Americans should just get over it, that Sally Hemings was Thomas Jefferson’s mistress. As a nation, we have yet to deal with the political, social, economic, and personal consequences of slavery.

Add to that the current sociopolitical climate, which has emboldened white supremacists and seen a sharp increase in hate crimes, and there is no good argument for making this show, especially given Benioff and Weiss’ track record on Game of Thrones. This show does not ask an interesting question about history, and I don’t think it should exist. I would, however, be interested in an alternate history of the United States in which Reconstruction continued past 1877, but I won’t hold my breath.